Type A vs Type B ADR Classifier

How to Use This Tool

Based on the characteristics described in the article, identify whether the adverse drug reaction described is Type A or Type B.

- Type A: Predictable, dose-dependent, common

- Type B: Unpredictable, not dose-dependent, rare but often severe

Case Scenario

When you take a medication, you expect it to help - not hurt. But sometimes, drugs cause unexpected or unwanted side effects. Not all of these reactions are the same. Some are common and predictable. Others are rare, dangerous, and totally unpredictable. Understanding the difference between Type A and Type B adverse drug reactions (ADRs) can make all the difference in avoiding harm, spotting trouble early, and knowing when to act.

Here’s the reality: about 85 to 90% of all drug side effects fall into Type A. That means most reactions you’ve probably experienced - like nausea from antibiotics or dizziness from blood pressure meds - are not surprises. They’re built into how the drug works. The other 10 to 15%? Those are Type B. These are the ones that catch doctors off guard. They can be life-threatening, happen to just one person out of 10,000, and have no clear link to the dose you took. This isn’t just theory. It’s happening in hospitals, clinics, and homes every day.

What Are Type A Adverse Drug Reactions?

Type A reactions are the predictable ones. They happen because of how the drug is supposed to work - just taken too far. Think of them as an extension of the drug’s intended effect, turned up too loud.

- Example: Taking too much acetaminophen? You risk liver damage. That’s not a fluke - it’s direct toxicity from exceeding the safe dose.

- Example: Starting a beta-blocker for high blood pressure? You might feel tired or have a slow heart rate. That’s the drug doing its job… too well.

- Example: NSAIDs like ibuprofen? Around 15-30% of users get stomach upset. That’s because these drugs block protective enzymes in the gut. It’s known. It’s expected.

These reactions are dose-dependent. Take more, get worse. Take less, it fades. That’s why doctors adjust doses. That’s why you’re told not to crush pills or double up. Type A reactions make up the bulk of side effects you see in prescribing guides. They’re why drug labels have warnings like “may cause drowsiness” or “avoid alcohol.”

They’re also why hospital pharmacies have automated alerts. If a patient’s kidney function is low and the system sees a dose of a kidney-cleared drug, it flags it. That’s Type A prediction in action.

What Are Type B Adverse Drug Reactions?

Type B reactions are the wild cards. They’re not related to the drug’s main action. They’re not dose-dependent. And they’re often immune-driven or tied to your unique biology.

- Example: A patient takes penicillin and goes into anaphylaxis - swelling, trouble breathing, drop in blood pressure. This happens in 0.01% to 0.05% of courses. No amount of dose adjustment helps. You can’t predict it by age, weight, or kidney function.

- Example: Sulfonamide antibiotics trigger Stevens-Johnson syndrome - a terrifying skin reaction that peels off like a burn. It affects roughly 1 to 6 people per million prescriptions. It’s not about the dose. It’s about your genes.

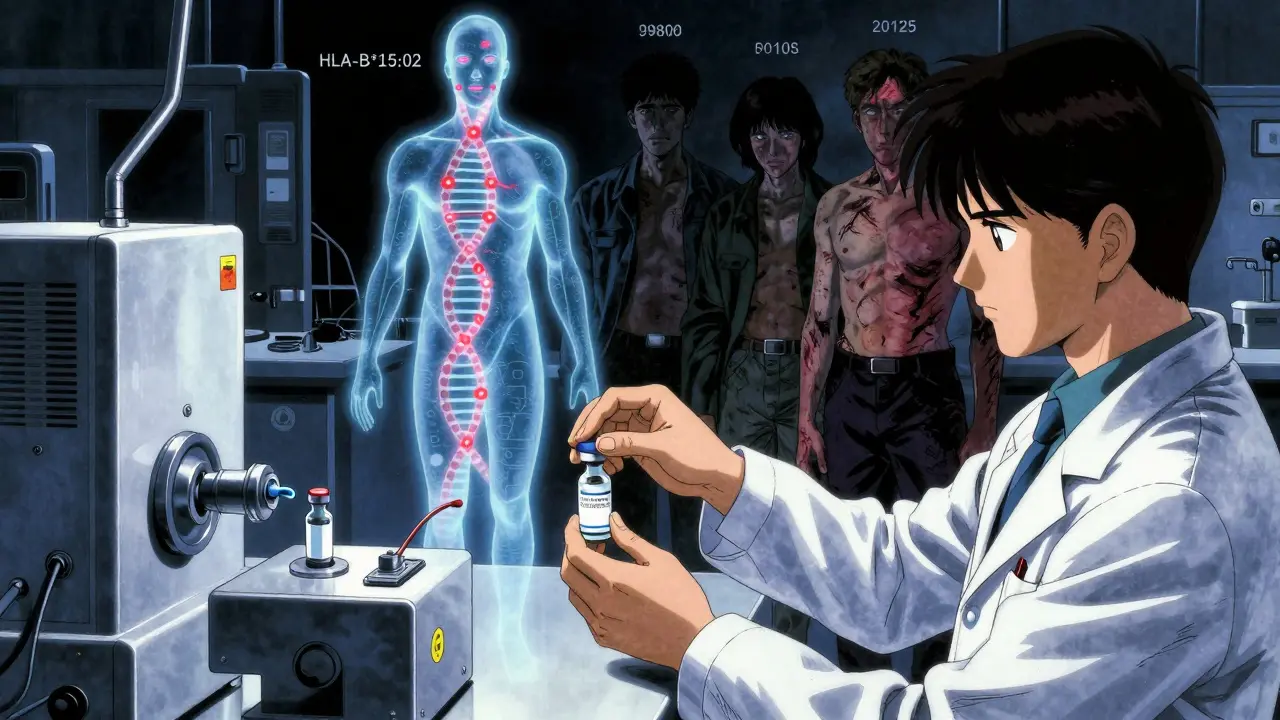

- Example: A healthy young adult takes a common anticonvulsant like carbamazepine and develops a severe rash. Turns out they carry the HLA-B*15:02 gene. That’s a genetic red flag. This used to be called “idiosyncratic.” Now we know it’s genetic.

Type B reactions are rare - but deadly. They cause 30% of all ADR-related hospitalizations. Even though they’re only 10-15% of all reactions, they’re responsible for most drug withdrawals from the market. Why? Because you can’t dose your way out of them. You can’t warn patients with a general label. You need to know who’s at risk - and that’s where things get complicated.

The Six-Type Classification System: Beyond A and B

The A/B system is useful, but it’s not enough. In 2023, most serious ADR reporting in Europe and the U.S. uses a six-type system that adds depth.

- Type C - Chronic effects from long-term use. Think corticosteroids. If you take more than 20mg of prednisone daily for over three weeks, you have a 20-30% chance of adrenal suppression. This isn’t sudden. It builds over time.

- Type D - Delayed reactions. The classic example? Diethylstilbestrol (DES). A drug given to pregnant women in the 1950s to prevent miscarriage. Decades later, their daughters developed a rare vaginal cancer. The damage didn’t show up until adulthood.

- Type E - Withdrawal reactions. Stop opioids? 80-90% of dependent patients get withdrawal symptoms within 12-30 hours. It’s not an allergic reaction. It’s the body’s physical dependence kicking in.

- Type F - Therapeutic failure. This one’s often missed. Rifampin, an antibiotic, speeds up how your liver breaks down oral contraceptives. Result? Birth control fails in 5-10% of cases. The drug worked - just not the way you thought.

These categories help explain reactions that don’t fit neatly into “dose-related” or “unpredictable.” A doctor who only thinks in Type A and Type B might miss a Type F interaction - and a patient could get pregnant because no one checked for drug interference.

Why the Classification Matters

It’s not just academic. Knowing the difference changes how you treat.

If it’s Type A - adjust the dose. Monitor. Educate. Maybe switch to a different drug in the same class.

If it’s Type B - stop the drug. Full stop. No second chances. Don’t try a lower dose. Don’t “see how it goes.” You’re not dealing with a side effect. You’re dealing with a potential death sentence.

And here’s the twist: modern science is blurring the lines. A reaction once labeled Type B - like carbamazepine-induced rash - is now known to be tied to specific genes. That means it’s not random anymore. We can test for it. We can prevent it. That’s why the FDA and WHO are pushing for pharmacogenomic screening before prescribing certain drugs.

But not every hospital can do genetic testing. Not every doctor has time. So the A/B framework still holds. It’s the first filter. The next step? Knowing when to dig deeper.

Real-World Challenges

Doctors don’t always agree on classification. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 physicians found that 67% struggled with ambiguous cases. Is a low sodium level from carbamazepine a Type A (dose-related) or Type B (idiosyncratic) reaction? Studies show it’s dose-dependent - so Type A. But if it only happens in people with a certain gene? Now it’s both.

And here’s the silent problem: Type F reactions - therapeutic failures - are missed in 25% of cases. A woman on birth control gets a prescription for rifampin. No one tells her. She gets pregnant. That’s not a side effect. That’s a system failure.

Meanwhile, Type B reactions like drug-induced liver injury or anaphylaxis are underreported. Patients don’t connect the dots. Clinicians assume it’s a virus or a flare-up. Only 65% of serious ADRs can be definitively classified - even with today’s tools.

What You Can Do

If you’re a patient:

- Know your meds. Ask: “What are the common side effects? What’s the rare but dangerous one?”

- Report anything unusual - even if it seems minor. A rash, dizziness, or unexplained fatigue could be the first sign.

- If you’ve had a bad reaction before, tell every new doctor. Write it down. Include the drug name and what happened.

If you’re a caregiver or healthcare provider:

- Use the six-type system. Don’t stop at A and B.

- Check for drug interactions. Especially with antibiotics, antifungals, and seizure meds.

- Consider pharmacogenomics for high-risk drugs - like abacavir, carbamazepine, or clopidogrel.

- Use automated alerts. Most hospital systems now flag Type A risks. Don’t ignore them.

The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to empower you. Most drug reactions are harmless and manageable. But the ones that aren’t? They often come without warning. Understanding the difference between Type A and Type B gives you a better chance to spot trouble before it’s too late.

What’s Next?

By 2027, experts predict 60% of what we now call Type B reactions will have known genetic causes. That means “idiosyncratic” will become “predictable.” We’ll test before we treat. We’ll prevent before we harm.

The World Health Organization is testing a new system that links genetic data directly to ADR alerts. The FDA is updating its reporting rules to require mechanistic details for every serious Type B reaction. And by 2025, the six-type classification will be the global standard.

But for now? The A/B split still saves lives. It’s simple. It’s clear. And when used right - with awareness of the deeper layers - it’s powerful.