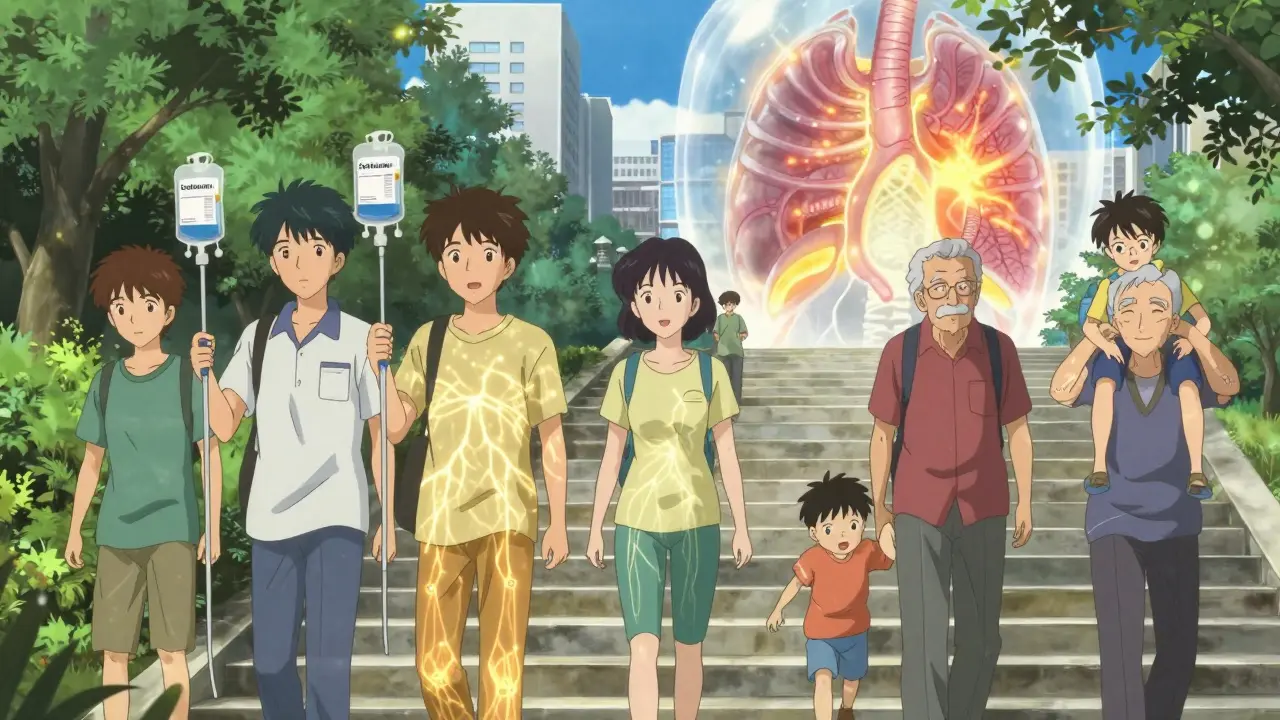

Myasthenia gravis isn’t just muscle weakness. It’s a breakdown in communication between nerves and muscles - a glitch in the body’s own wiring. Every time you try to lift your arm, blink your eye, or swallow food, your immune system mistakenly attacks the connection point - the neuromuscular junction - leaving you exhausted, frustrated, and often misunderstood. For decades, treatment meant managing symptoms with pills that made you feel worse than the disease. But today, that’s changing. New therapies are turning myasthenia gravis from a lifelong struggle into a manageable condition - even for those who once had no options.

How Myasthenia Gravis Actually Works

At its core, myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease. Your immune system, designed to fight viruses and bacteria, turns on itself. It produces antibodies that block or destroy receptors for acetylcholine - the chemical messenger that tells your muscles to contract. Without that signal, muscles tire quickly. Eyelids droop. Chewing becomes hard. Breathing grows shallow. Symptoms get worse with activity and improve with rest - a telltale sign doctors look for.

Not everyone has the same antibodies. About 85% of people with generalized myasthenia gravis test positive for antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR). Around 5-8% have antibodies against MuSK, a different protein involved in nerve-muscle signaling. And 5-10% are seronegative - no known antibodies detected, but symptoms still match. This matters because treatment depends on which type you have.

The disease was first described in 1672, but real progress didn’t start until 1973, when scientists identified the first autoantibody. That discovery changed everything. Suddenly, it wasn’t just a mystery - it was a target.

First-Line Treatments: Symptomatic Relief and Immunosuppression

Most patients start with pyridostigmine (Mestinon), a drug that slows the breakdown of acetylcholine. It doesn’t fix the immune problem - it just gives the remaining signals a better chance to work. Doses range from 60 to 120 mg every 3 to 6 hours. About 35-45% of people get stomach cramps, nausea, or diarrhea from it. It’s not a cure, but it helps people get through the day.

Then comes prednisone. This corticosteroid suppresses the immune system broadly. It works fast - 70-80% of patients see improvement within weeks. But the cost is high. Weight gain hits 65% of users. Osteoporosis develops in 25% after just one year. Diabetes appears in 15-20%. Many patients stop taking it because the side effects feel worse than the disease.

That’s why doctors add slow-acting immunosuppressants. Azathioprine (2-3 mg/kg/day) and mycophenolate mofetil (1,000-1,500 mg twice daily) take 6 to 18 months to kick in, but they’re better for long-term use. Azathioprine can cause low white blood cell counts in 10% of people. Mycophenolate gives 30% gastrointestinal trouble. Cyclosporine works in 90% of cases, but 30% develop high blood pressure and 25% get kidney damage. These drugs are cheap - $500 to $2,000 a year - but they’re not easy to live with.

Thymectomy: Removing the Source

The thymus gland, tucked behind the breastbone, plays a role in training immune cells. In myasthenia gravis, it often goes rogue - producing the very antibodies that attack muscles. Removing it - a thymectomy - isn’t just surgery. It’s a reset button.

The landmark MGTX trial in 2016 proved it. Patients who had thymectomy along with prednisone had 56% less steroid exposure and 67% fewer hospitalizations over three years compared to those on prednisone alone. Five years later, 35-40% of AChR-positive patients achieved complete stable remission - compared to just 15-20% with medication alone.

Today, most neurologists recommend thymectomy for AChR-positive patients aged 18 to 65 within 6 to 12 months of diagnosis. Minimally invasive techniques - robotic or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery - are now common. But long-term outcomes for these newer methods are still being studied. Recovery takes weeks. Fatigue lingers for many. Still, for those who respond, it’s life-changing.

The New Generation: Targeted Biologics

The biggest shift in myasthenia gravis treatment happened in the last five years. Seven FDA-approved targeted therapies now exist - drugs that don’t just suppress the immune system, but surgically remove the bad actors.

Complement inhibitors like eculizumab and ravulizumab block a specific part of the immune system that destroys the neuromuscular junction. Eculizumab requires weekly IV infusions for four weeks, then every two weeks. It’s highly effective - 88% of patients improve, and over half reach minimal manifestation status. But there’s a catch: you must get vaccinated against meningococcus before starting. These drugs cost $500,000 to $600,000 a year. Insurance denials are common.

FcRn inhibitors are the new stars. Efgartigimod, rozanolixizumab, nipocalimab, and batoclimab all work by lowering IgG antibodies - the type that cause myasthenia gravis. They work fast - improvement in 1 to 2 weeks. They work across antibody types, including seronegative cases. The 2024 ADAPT SERON study showed 68% of seronegative patients responded to efgartigimod - a breakthrough for those previously left out.

Rozanolixizumab is given as a weekly under-the-skin injection. Efgartigimod is IV, every week for four weeks, then repeated every few months. Nipocalimab, approved in April 2025, works monthly and is now available for teens as young as 12. Batoclimab, with results published in early 2025, shows similar results to efgartigimod but with less frequent dosing.

Patients report better quality of life. A 2025 survey found 78% of users on FcRn inhibitors saw major improvement. Sixty-two percent prefer the subcutaneous options for convenience, even with more injection site reactions.

Rituximab and Other Options

Rituximab, a B-cell depleter, is a powerful tool - especially for MuSK-positive myasthenia gravis. It works in 80% of those patients. For AChR-positive, the response drops to 50-60%. It’s given as two IV doses two weeks apart, or four weekly doses. Cost? $10,000 to $15,000 per course. But it takes 8 to 16 weeks to work. That’s slow compared to FcRn inhibitors.

Plasmapheresis and IVIG are rescue tools. Plasmapheresis removes antibodies directly from the blood - five sessions over 7 to 10 days. IVIG floods the system with healthy antibodies to neutralize the bad ones. Both work fast - within days. But effects last only weeks to months. They’re used for sudden worsening - a myasthenic crisis - or to prepare for surgery.

Choosing the Right Path

There’s no one-size-fits-all. Treatment depends on antibody status, age, severity, and lifestyle.

For mild cases: Start with pyridostigmine and a low-dose steroid. Add azathioprine or mycophenolate if needed.

For moderate to severe AChR-positive: Thymectomy within a year, then consider FcRn inhibitors or complement inhibitors if symptoms persist.

For MuSK-positive: Rituximab is often second-line. Some neurologists start it earlier - Nordic guidelines say it leads to faster improvement.

For seronegative: FcRn inhibitors are now the best option. Efgartigimod and rozanolixizumab have proven results where older drugs failed.

Cost and access matter. Insurance often blocks biologics unless you’ve tried two immunosuppressants first. The process can take 3 to 6 months. Many patients give up.

What’s Coming Next

The future is personalized. Researchers are developing blood tests that track disease activity better than antibody levels - because antibodies don’t always match symptoms. IgG4-specific assays, expected in 2026, could tell you exactly when to adjust treatment.

Early trials are testing agrin mimetics - drugs that protect the neuromuscular junction from damage. Another experimental approach: CAR T-cell therapy. Memorial Sloan Kettering’s 2025 trial targeted B-cells in refractory cases. Sixty percent of patients went into remission at six months.

And for older patients? That’s the next frontier. Thirty percent of people with myasthenia gravis are over 65. They often have heart disease, diabetes, or kidney issues. Current drugs aren’t designed for them. New protocols are being tested to balance safety and effectiveness.

Living With Myasthenia Gravis Today

It’s not perfect. Fatigue remains a silent burden. A 2024 study found 55% of patients on long-term prednisone reported severe quality-of-life loss. Those on FcRn inhibitors? Only 25% did.

Support matters. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America offers a 24/7 nurse hotline - answered within three minutes 95% of the time. There are 147 local support groups across the U.S. connecting 15,000 people each year.

Patients are speaking up. On Reddit, 75% of posts about eculizumab mention insurance battles. On forums, people share tips on managing side effects, finding specialists, and navigating disability paperwork.

Myasthenia gravis is no longer a death sentence. It’s not always easy. But the tools to live well - to work, to travel, to hug your kids - are here. And they’re getting better every year.

Can myasthenia gravis be cured?

There’s no universal cure, but many people achieve long-term remission. About 35-40% of AChR-positive patients who have thymectomy reach complete stable remission within five years. Others maintain minimal manifestation status - meaning symptoms are nearly gone - with targeted biologics. Some stop all medication and stay well. But relapses can happen, so ongoing monitoring is key.

How do I know if my treatment is working?

Doctors use standardized scores like MG-ADL (Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living) and QMG (Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis). These track things like eyelid strength, speech clarity, and ability to climb stairs. Improvement shows up in these scores weeks before antibody levels change. Regular check-ins every 4 to 12 weeks help adjust treatment before symptoms spiral.

Are biologics safe for long-term use?

Yes, current data shows they’re safe for years. Eculizumab has been used for over a decade in some patients with no new safety signals beyond the known meningococcal risk. FcRn inhibitors like efgartigimod and rozanolixizumab have shown sustained safety in trials lasting up to three years. The biggest risk is infection - but not from the drug itself. It’s from lowering protective antibodies. Vaccinations and monitoring are critical.

Why do some people not respond to treatment?

Some have seronegative myasthenia gravis - no detectable antibodies - making targeted therapies harder to predict. Others may have different immune pathways not yet understood. A small group develops resistance to certain drugs. In these cases, doctors may combine therapies - like adding FcRn inhibitors to low-dose rituximab. Clinical trials are exploring new targets, including T-cells and nerve repair mechanisms.

What should I do if I’m having a myasthenic crisis?

A myasthenic crisis is a medical emergency - when breathing muscles fail. Call 911 immediately. Do not wait. In the hospital, you’ll get IVIG or plasmapheresis to quickly remove antibodies. You may need mechanical ventilation. Once stabilized, your treatment plan will be reviewed and adjusted to prevent future crises. Having an emergency plan with your neurologist - including contact numbers and medication list - saves lives.

Can I get pregnant if I have myasthenia gravis?

Yes, but it requires careful planning. Pregnancy can worsen symptoms, especially in the first trimester and postpartum. Some drugs like mycophenolate and rituximab are unsafe during pregnancy. FcRn inhibitors are not yet proven safe - European guidelines require pregnancy testing before starting. Work with a neurologist and high-risk OB to switch to safer options like pyridostigmine and prednisone before conception. Most women deliver healthy babies with proper management.

Is myasthenia gravis hereditary?

No, it’s not inherited like cystic fibrosis or Huntington’s. But having a family member with an autoimmune disease - like lupus, thyroiditis, or type 1 diabetes - may slightly increase your risk. Genetics play a background role, but triggers like infections, stress, or medications are usually needed to start the disease. Most patients have no family history.

How often do I need blood tests?

It depends on your treatment. If you’re on azathioprine or cyclosporine, you need monthly blood tests for liver and kidney function and blood counts. For FcRn inhibitors or complement blockers, tests are less frequent - usually every 3 months to check for infections and general health. Antibody levels aren’t used to monitor treatment anymore - they don’t reflect how you feel. Symptom scores and functional tests are more important.

Ajay Brahmandam

December 22, 2025 AT 07:58Been on efgartigimod for 8 months now. My eyelids don’t droop anymore when I wake up. No more slurpy speech at work. I can carry groceries without needing a nap after. Still gotta get IVs every 6 weeks, but honestly? Worth every prick.

My insurance fought it for 5 months. Filed 3 appeals. Got a nurse from MGFA to write a letter. Won. If you’re reading this and stuck - don’t give up. You’re not alone.

Sam Black

December 23, 2025 AT 05:20They say ‘manageable’ like it’s a checkbox. But try explaining to your boss why you need to lie down after typing an email. Or why your kid’s birthday party feels like a triathlon.

Biologics are miracles - but they don’t fix the guilt of being the person who ‘just needs to push harder.’

Also, the cost? It’s not a number. It’s a whole other life you didn’t sign up for.

Herman Rousseau

December 24, 2025 AT 21:03Just wanted to say THANK YOU for this post. Seriously. I’ve been lurking for months, too scared to ask anything. This is the first time I’ve felt like someone actually gets it.

My neuro just put me on rozanolixizumab last week. Injections hurt, but my legs haven’t given out since. Still getting used to the idea that I might not always feel like a ghost in my own body. 🙏

Jeremy Hendriks

December 26, 2025 AT 13:43They call this progress? You’re telling me we’ve spent 50 years treating symptoms while the real enemy - the thymus, the IgG, the broken wiring - was staring us in the face?

And now we’re giving people IVs that cost more than a Tesla? This isn’t medicine. It’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

Jim Brown

December 28, 2025 AT 08:19There’s a quiet tragedy in the fact that the most effective treatments are also the most inaccessible. We’ve cracked the biology - but not the human infrastructure.

Science doesn’t care about insurance forms. It doesn’t care if you’re 67 and on Medicare with a kidney transplant. It just gives us tools - and then leaves us to fight the system with bare hands.

Maybe the real cure isn’t in the lab. Maybe it’s in the collective scream of patients who refuse to be invisible.

Candy Cotton

December 30, 2025 AT 02:34Why are we even talking about this? In America, we have the best medicine in the world. If you can’t afford it, you’re not trying hard enough. Get a second job. Sell your car. Move to Mexico. There are clinics there for $500. This isn’t a medical crisis - it’s a personal responsibility failure.

Vikrant Sura

December 30, 2025 AT 10:5488% improvement? That’s marketing. The real number is 20% who actually get to keep the treatment after insurance denies it. Also, thymectomy? 35% remission? That’s just a fancy word for ‘maybe you’ll get lucky.’

Most of this is placebo with IVs.

Tarun Sharma

December 31, 2025 AT 23:55Thank you for the detailed overview. In India, access to FcRn inhibitors is nearly impossible. We rely on pyridostigmine and azathioprine. Many patients stop treatment due to cost. The human cost is higher than the financial one.

Gabriella da Silva Mendes

January 1, 2026 AT 10:35Okay but have you considered that maybe the immune system is trying to tell us something? Like… maybe we’re too clean? Too processed? Too digital? Maybe myasthenia is our body’s way of saying: STOP. BREATHE. TOUCH GRASS.

I tried a 30-day juice cleanse and my eyelids stopped drooping for 2 weeks. Coincidence? I think not. 🌿✨

Also, glyphosate. It’s always glyphosate.

Jamison Kissh

January 2, 2026 AT 00:35What if the real breakthrough isn’t the drug - but the shift in how we see the patient? Not as a case study. Not as a cost center. But as someone who’s been waiting decades for someone to say: ‘I see you. And you deserve more than survival.’

The science is dazzling. But the humanity? That’s the real cure.

Aliyu Sani

January 3, 2026 AT 00:25Yo. I’m from Nigeria. We don’t even have pyridostigmine in some states. My cousin’s sister has MG. She uses a stick to lift her eyelids. No IVs. No biologics. Just prayer and patience.

Y’all talking about insurance like it’s a luxury. Here, it’s just… not existing.

But still. We breathe. We blink. We love.

Julie Chavassieux

January 4, 2026 AT 04:59They said it was incurable. Then they said it was manageable. Now they say it’s ‘remissible.’

When do we get to say: it’s gone?

When do we get to live without the shadow of the next crisis?

When do we get to forget we’re sick?

jenny guachamboza

January 4, 2026 AT 19:13EVERYTHING IS A LIE. The FDA is owned by Big Pharma. The thymectomy trials? Faked. The antibodies? A hoax. They’re using MG to sell drugs so they can buy more yachts.

Also, 5G causes autoimmunity. I know a guy. His dog got MG after the new cell tower went up. Coincidence? I think not. 🚨📡

And why are they always targeting IgG? What about IgE? They’re hiding it. I’ve seen the documents.

Nader Bsyouni

January 5, 2026 AT 06:14It’s fascinating how we’ve elevated a neuromuscular disorder to the status of a cultural narrative. The suffering is real, yes. But the language around it? It’s been commodified into a hero’s journey.

‘You’re not broken - you’re just misunderstood.’

How poetic. How useless. The synapse doesn’t care about your TED Talk.

Cara Hritz

January 6, 2026 AT 07:18Wait so if you have MuSK positive you dont get thymectomy? But what if you have both? I think I read somewhere that thymus is just a red herring and the real issue is the gut microbiome??

Also my cousin's neighbor's cousin took a supplement called 'NeuroCalm' and her symptoms vanished in 3 days. Why isn't this on the FDA website??