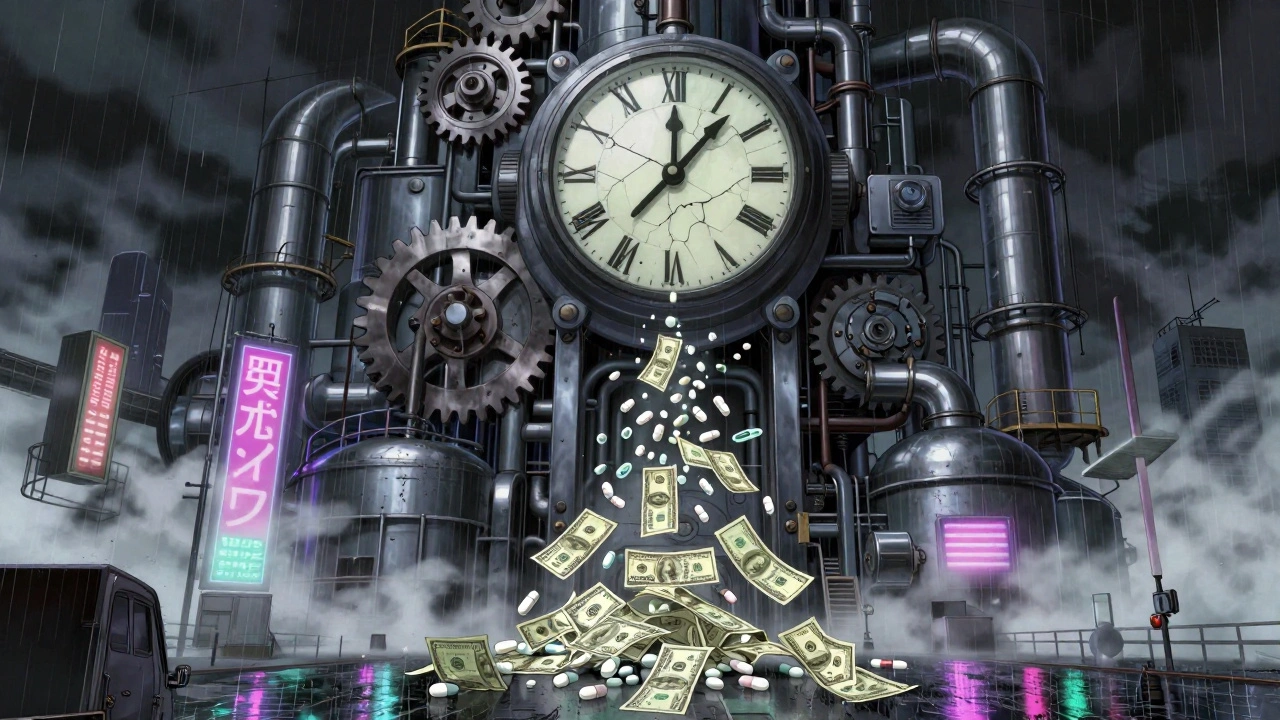

When a drug’s patent runs out, prices don’t just dip-they crash. It’s one of the clearest examples of how competition reshapes markets. Take apixaban, the blood thinner sold as Eliquis. Before its patent expired in 2020, patients in the U.S. paid around $850 a month out of pocket. A year later, the generic version cost $10. That’s not a sale. That’s a collapse. And it’s not an exception. It’s the rule.

Why Patents Exist-and Why They End

Pharmaceutical patents give companies a 20-year window to recoup the cost of research and development. Developing a new drug can cost over $2 billion and take more than a decade. Without patent protection, companies wouldn’t invest. But once that 20-year clock runs out, the law opens the door for others to make the same drug. That’s the trade-off: innovation now, affordability later. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the modern system that balances this. It lets generic manufacturers apply to sell the same drug without repeating expensive clinical trials. All they need to prove is that their version works the same way. This system was designed to cut prices fast. And it usually does.How Prices Really Drop-It’s Not Linear

The moment the first generic hits the market, prices start falling. But the biggest drops don’t happen right away. They come later. - The first generic usually cuts the price by 15% to 20%.- The second and third generics push it down another 30% to 50%.

- By the time five or more companies are selling the same drug, prices often fall 80% or more. A 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum tracked 505 drugs across eight countries. In the U.S., prices fell 32% in the first year after patent expiration and 82% over eight years. In Australia, the drop was 64%. In Switzerland, it was only 18%. Why the difference? It’s not about the drug. It’s about the system.

Country by Country: Who Gets the Biggest Savings?

The U.S. leads in price drops-not because it’s more generous, but because it’s more competitive. There are no government price controls. Once generics enter, pharmacies and insurers shop for the cheapest option. That drives prices down fast. Europe works differently. Countries like Germany and France use reference pricing. If a generic is cheaper than the brand, insurers pay only the generic price. That pushes manufacturers to lower prices early. But the process is slower. Generic entry takes 12 to 18 months in Europe. In the U.S., it’s about 30 months on average. Japan and the UK fall in between. Canada saw a 48% price drop after eight years. Australia’s 64% drop shows that even with some regulation, competition still wins.

The Exception: Biologics and Patent Thickets

Not all drugs follow the same path. Biologics-complex drugs made from living cells, like Humira or Ozempic-are harder to copy. That’s why they get extra protection. Humira, for example, had its original patent expire in 2016. But AbbVie filed over 130 secondary patents on minor changes-dosage, delivery methods, packaging. These didn’t make the drug better. They just blocked competitors. Generic versions didn’t meaningfully enter the market until January 2023, seven years later. The same happened with Eliquis and Ozempic. Even though the base patent expired in 2020 and 2026 respectively, manufacturers piled on dozens of additional patents. According to I-MAK’s 2025 report, blockbuster drugs now average 10 to 15 secondary patents. These extend market control by 12 to 14 years beyond the original term. This is called a “patent thicket.” It’s legal. But it’s not what the system was meant for.Who Pays the Price? Patients, Insurers, and Hospitals

When prices drop, savings flow to different places. In the U.S., Medicare and private insurers get the biggest cuts. Patients see lower copays. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found 68% of insured adults paid less after generics arrived. But here’s the catch: formularies matter. Even if a generic is cheaper, your insurance might not cover it right away. Some insurers keep the brand drug on their preferred list because of rebates from the manufacturer. That’s what happened with Humira biosimilars in 2023. The generics were available. But many patients still paid full price because their plan didn’t switch. Doctors notice it too. Rheumatologist Dr. Sarah Kim in Chicago says she saw rapid adoption of biosimilars for infliximab after 2016. For Humira? “The transition has been slow,” she says. “Payers are locked into contracts.”

Manufacturers Fight Back-With Legal Tricks and New Formulations

Originator companies aren’t sitting still. When a patent expires, they often launch a “reformulated” version-new pill shape, extended release, different packaging. Sometimes it’s better. Sometimes it’s just a trick to keep patients on the brand. They also bundle deals with pharmacies and insurers. If a hospital agrees to buy 90% of its Humira from AbbVie, they get a discount. That makes it harder for generics to compete, even if they’re cheaper. The result? In 2023, 78% of new patents filed for drugs weren’t for new medicines. They were for old ones. And 70% of the top 100 prescribed drugs had their exclusivity extended at least once.What’s Changing? Regulatory Pressure Is Growing

Governments are starting to push back. In 2023, the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act let Medicare negotiate prices for some high-cost drugs. That gave manufacturers a new incentive: delay generic entry to avoid negotiation. The FDA approved 870 generic drugs in 2023-a 12% jump from 2022. They’re prioritizing complex generics that used to take years to approve. The European Union’s 2024 Pharmaceutical Package proposes limiting how long companies can extend patents with supplementary certificates. The U.S. Patent Office has also started reviewing “patent thickets” more closely. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that generic and biosimilar competition will save the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion over the next decade. But I-MAK warns: without reform, those savings will be delayed by an average of 4.2 years per drug.The Bottom Line: Competition Works-If It’s Allowed

Patent expiration isn’t magic. It’s economics. When more companies can sell the same thing, prices fall. The more competitors, the faster and deeper the drop. The system works best when:- Generic manufacturers can enter quickly

- There are no legal roadblocks like patent thickets

- Insurers and pharmacies are free to choose the cheapest option

- Patients aren’t locked into expensive brands by rebates or contracts

When a drug’s patent ends, the market doesn’t just change. It resets. And for patients, that reset can mean the difference between paying $800 a month-or $10.

Aidan Stacey

December 12, 2025 AT 10:16This is wild. $850 to $10? That’s not capitalism, that’s a heist with a patent as the mask. I’ve seen people skip doses just to make it last. This isn’t about innovation anymore-it’s about who gets to live.

Eddie Bennett

December 13, 2025 AT 20:52It’s funny how the same people screaming about free markets get mad when the market actually works. Patents were meant to be temporary. The fact that we need to explain this like it’s news says everything.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

December 15, 2025 AT 01:32The JAMA study data is solid, but what’s rarely discussed is how pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) profit from the gap. They take rebates from brand-name drugs even after generics are cheaper. So the savings never reach patients. It’s not just patents-it’s the whole middleman circus.

Aman deep

December 17, 2025 AT 00:42in india we get generics like candy. i paid $2 for apixaban last year. no joke. but here’s the thing-sometimes the quality is sketchy. not all generics are equal. i’ve seen folks get sick from bad batches. so yeah, price drop is amazing but dont forget the safety net. we need better global standards, not just cheaper pills.

Taylor Dressler

December 17, 2025 AT 23:47One thing people overlook: the Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just lower prices-it created an entire industry of generic manufacturers that now employ hundreds of thousands. The system works because it incentivizes both innovation and access. The problem isn’t the law-it’s the loopholes. Patent thickets? That’s corporate greed dressed up as legal strategy. We need the FDA and FTC to crack down harder on evergreening.

And yes, the U.S. leads in price drops because we have no price controls. But that’s also why we have the highest out-of-pocket costs in the world. It’s a paradox: the market works too well for insurers and too poorly for patients.

Doctors aren’t to blame. Most want generics. But if your insurance’s formulary still pushes the brand because of rebates, you’re stuck. That’s not market competition-that’s collusion.

When I worked in pharmacy, we’d get calls from patients crying because they couldn’t afford their meds. Then the generic hits, and suddenly they’re back in control of their lives. That’s the real win. Not the stock price. Not the quarterly report. Real people.

Let’s not romanticize Europe. Their slower drop isn’t nobility-it’s bureaucracy. Australia’s 64% drop? That’s the sweet spot: regulated competition. No patents extended, no rebates hiding in the shadows, just fair access.

And biologics? They’re the new frontier. Humira’s 130 patents? That’s not innovation. That’s a legal landmine. We need legislation to cap secondary patents. One per drug. Max. No more.

The $1.7 trillion savings? That’s not a number. That’s thousands of diabetics not choosing between insulin and rent. That’s cancer patients getting treatment instead of debt. This isn’t policy. It’s morality.

Mia Kingsley

December 19, 2025 AT 09:59lol you think this is about patients? nah. it’s about pharma execs losing their yachts. the real crime is that we let them get away with it for 20 years. now they’re mad because the party’s over.

Kristi Pope

December 20, 2025 AT 18:55I’ve watched this play out with my dad’s heart meds. First year after patent expiry, price dropped 60%. Second year, another 30%. Now it’s 85% cheaper. He’s alive because of it. But I’ve seen people get stuck with the brand because their doctor didn’t know the generic was approved. We need better education. Not just for patients-for doctors too.

And don’t even get me started on the pharmacy chains that still push the brand because they get kickbacks. It’s disgusting. But hey, at least we’re talking about it now.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 22, 2025 AT 05:53It’s beautiful when you think about it. A molecule doesn’t care who made it. If it works, it works. The system was built on that truth. Now we’ve turned it into a chess game with lawyers and lobbyists. But the people? They just want to breathe. And that’s worth fighting for.

Jean Claude de La Ronde

December 24, 2025 AT 04:48so the usa has the fastest price drops because it has no regulations? brilliant. so we’re the land of the free… as long as you’re rich enough to survive the free market. thanks for the laugh, america. you’re a masterpiece of chaos.

Monica Evan

December 25, 2025 AT 13:48my cousin in canada paid 400 for the brand then 70 for the generic. still too much. but in mexico? 15 bucks. no joke. why do we even have this system? why not just let global prices set the floor? we’re not smarter. we’re just greedier.

Vivian Amadi

December 26, 2025 AT 23:02you’re all ignoring the real issue: the FDA approves generics too fast. half of them are garbage. people die because they get a cheap pill that doesn’t dissolve right. stop pretending this is a win.

Jim Irish

December 27, 2025 AT 08:01Patents are a social contract. Society grants monopoly to incentivize innovation. When that monopoly becomes permanent through legal manipulation, the contract is broken. The system must be restored to its original intent: protect innovation, not profit.

john damon

December 29, 2025 AT 01:10👏👏👏 this is why we need to defund pharma 🏛️💸 #GenericRevolution #PatientsOverProfits

Lisa Stringfellow

December 30, 2025 AT 00:01So let me get this straight… the system works? Really? Then why do people still die because they can’t afford meds? You’re all just patting yourselves on the back like this is a victory. It’s not. It’s a tragedy with a spreadsheet.

Ariel Nichole

December 30, 2025 AT 21:26It’s kind of amazing how one simple idea-competition-can fix something so broken. No magic. No miracle drug. Just more companies making the same thing. Sometimes the simplest solutions are the hardest to accept.